Ashok Maurya or Ashoka (Devanāgarī: अशोक, IAST: Aśoka, IPA: [aˈɕoːkə], ca. 304–232 BC), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was an Indian emperor of the Maurya Dynasty who ruled almost all of the Indian subcontinent from ca. 269 BC to 232 BC.[1] One of India's greatest emperors, Ashoka reigned over most of present-day India after a number of military conquests. His empire stretched from present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan in the west, to the present-day Bangladesh and the Indian state of Assam in the east, and as far south as northern Kerala and Andhra Pradesh. He conquered the kingdom named Kalinga, which no one in his dynasty had conquered starting from Chandragupta Maurya. His reign was headquartered in Magadha (present-day Bihar, India). He embraced Buddhism from the prevalent Hindu tradition after witnessing the mass deaths of the war of Kalinga, which he himself had waged out of a desire for conquest. He was later dedicated to the propagation of Buddhism across Asia and established monuments marking several significant sites in the life of Gautama Buddha. Ashoka was a devotee of ahimsa (nonviolence), love, truth, tolerance and vegetarianism. Ashoka is remembered in history as a philanthropic administrator. In the history of India, Ashoka is referred to as Samraat Chakravartin Ashoka - the Emperor of Emperors Ashoka.

His name "aśoka" means "painless, without sorrow" in Sanskrit (the a privativum and śoka "pain, distress"). In his edicts, he is referred to as Devānāmpriya (Pali Devānaṃpiya or "The Beloved Of The Gods"), and Priyadarśin (Pali Piyadasī or "He who regards everyone with affection").

Along with the Edicts of Ashoka, his legend is related in the later 2nd century Aśokāvadāna ("Narrative of Asoka") and Divyāvadāna ("Divine narrative"), and in the Sri Lankan text Mahavamsa ("Great Chronicle").

Ashoka played a critical role in helping make Buddhism a world religion.[2] As the peace-loving ruler of one of the world's largest, richest and most powerful multi-ethnic states, he is considered an exemplary ruler, who tried to put into practice a secular state ethic of non-violence. The emblem of the modern Republic of India is an adaptation of the Lion Capital of Ashoka.

Contents[hide] |

Biography

Early life

Ashoka was born to the Mauryan emperor Bindusara and his queen, Dharmā [or Dhammā]. Ashokāvadāna states that his mother was a queen named Subhadrangī, the daughter of Champa of Telangana. Queen Subhadrangī was a Brahmin of the Ajivika sect. Sage Pilindavatsa (aias Janasana) was a kalupaga Brahmin[3] of the Ajivika sect had found Subhadrangī as a suitable match for Emperor Bindusara. A palace intrigue kept her away from the king. This eventually ended, and she bore a son. It is from her exclamation "I am now without sorrow", that Ashoka got his name. The Divyāvadāna tells a similar story, but gives the name of the queen as Janapadakalyānī.[4][5]

Ashoka had several elder siblings, all of whom were his half-brothers from other wives of Bindusāra.

He had been given the royal military training knowledge. He was a fearsome hunter, and according to a legend, he killed a lion with just a wooden rod. He was very adventurous and a trained fighter, who was known for his skills with the sword. Because of his reputation as a frightening warrior and a heartless general, he was sent to curb the riots in the Avanti province of the Mauryan empire.[6]

Rise to power

The Divyavandana refers to Ashoka putting down a revolt due to activities of wicked ministers. This may have been an incident in Bindusara's times. Taranatha's account states that Chanakya, one of Bindusara's great lords, destroyed the nobles and kings of 16 towns and made himself the master of all territory between the eastern and the western seas. Some historians consider this as an indication of Bindusara's conquest of the Deccan while others consider it as suppression of a revolt. Following this Ashoka was stationed at Ujjayini as governor.[5]

Bindusara's death in 273 BC led to a war over succession. According to Divyavandana, Bindusara wanted his son Sushim to succeed him but Ashoka was supported by his father's ministers. A minister named Radhagupta seems to have played an important role. One of the Ashokavandana states that Ashoka managed to become the king by getting rid of the legitimate heir to the throne, by tricking him into entering a pit filled with live coals. The Dipavansa and Mahavansa refer to Ashoka killing 99 of his brothers, sparing only one, named Tissa.[5] Although there is no clear proof about this incident. The coronation happened in 269 BC, four years after his succession to the throne.

Early life as Emperor

Ashoka is said to have been of a wicked nature and bad temper. He submitted his ministers to a test of loyalty and had 500 of them killed. He also kept a harem of around 500 women. Once when certain lot of these women insulted him, he had the whole lot of them burnt to death. He also built hell on earth, an elaborate and horrific torture chamber. This torture Chamber earned him the name of Chand Ashoka (Sanskrit), meaning Ashoka the Fierce.[5]

Ascending the throne, Ashoka expanded his empire over the next eight years, from the present-day boundaries and regions of Burma–Bangladesh and the state of Assam in India in the east to the territory of present-day Iran / Persia and Afghanistan in the west; from the Pamir Knots in the north almost to the peninsular of southern India (i.e. Tamilnadu / Andhra pradesh).[5]

Conquest of Kalinga

While the early part of Ashoka's reign was apparently quite bloodthirsty, he became a follower of the Buddha's teaching after his conquest of Kalinga on the east coast of India in the present-day states of southern Orissa and north coastal Andhra Pradesh. Kalinga was a state that prided itself on its sovereignty and democracy. With its monarchical parliamentary democracy it was quite an exception in ancient Bharata where there existed the concept of Rajdharma. Rajdharma means the duty of the rulers, which was intrinsically entwined with the concept of bravery and Kshatriya dharma. The Kalinga War happened eight years after his coronation. From his 13th inscription, we come to know that the battle was a massive one and caused the deaths of more than 100,000 soldiers and many civilians who rose up in defense; over 150,000 were deported.[7] When he was walking through the grounds of Kalinga after his conquest, rejoicing in his victory, he was moved by the number of bodies strewn there and the wails of the kith and kin of the dead.

Buddhist conversion

| | This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2009) |

As the legend goes, one day after the war was over, Ashoka ventured out to roam the city and all he could see were burnt houses and scattered corpses. This sight made him sick and he cried the famous monologue:

What have I done? If this is a victory, what's a defeat then? Is this a victory or a defeat? Is this justice or injustice? Is it gallantry or a rout? Is it valor to kill innocent children and women? Do I do it to widen the empire and for prosperity or to destroy the other's kingdom and splendor? One has lost her husband, someone else a father, someone a child, someone an unborn infant.... What's this debris of the corpses? Are these marks of victory or defeat? Are these vultures, crows, eagles the messengers of death or evil?

The brutality of the conquest led him to adopt Buddhism, and he used his position to propagate the relatively new religion to new heights, as far as ancient Rome and Egypt. He made Buddhism his state religion around 260 BC, and propagated it and preached it within his domain and worldwide from about 250 BC. Emperor Ashoka undoubtedly has to be credited with the first serious attempt to develop a Buddhist policy.

Prominent in this cause were his son Venerable Mahindra and daughter Sanghamitra (whose name means "friend of the Sangha"), who established Buddhism in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He built thousands of Stupas and Viharas for Buddhist followers. The Stupas of Sanchi are world famous and the stupa named Sanchi Stupa was built by Emperor Ashoka. During the remaining portion of Ashoka's reign, he pursued an official policy of nonviolence (ahimsa). Even the unnecessary slaughter or mutilation of animals was immediately abolished. Everyone became protected by the king's law against sport hunting and branding. Limited hunting was permitted for consumption reasons but Ashoka also promoted the concept of vegetarianism. Ashoka also showed mercy to those imprisoned, allowing them leave for the outside a day of the year. He attempted to raise the professional ambition of the common man by building universities for study, and water transit and irrigation systems for trade and agriculture. He treated his subjects as equals regardless of their religion, politics and caste. The kingdoms surrounding his, so easily overthrown, were instead made to be well-respected allies.

He is acclaimed for constructing hospitals for animals and renovating major roads throughout India. After this transformation, Ashoka came to be known as Dhammashoka (Sanskrit), meaning Ashoka, the follower of Dharma. Ashoka defined the main principles of dharma (dhamma) as nonviolence, tolerance of all sects and opinions, obedience to parents, respect for the Brahmans and other religious teachers and priests, liberality towards friends, humane treatment of servants, and generosity towards all. These principles suggest a general ethic of behaviour to which no religious or social group could object.

Some critics say that Ashoka was afraid of more wars, but among his neighbors, including the Seleucid Empire and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom established by Diodotus I, none could match his strength. He was a contemporary of both Antiochus I Soter and his successor Antiochus II Theos of the Seleucid dynasty as well as Diodotus I and his son Diodotus II of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. If his inscriptions and edicts are well studied one finds that he was familiar with the Hellenic world but never edicts, which talk of friendly relations, give the names of both Antiochus of the Seleucid empire and Ptolemy III of Egypt. The fame of the Mauryan empire was widespread from the time that Ashoka's grandfather Chandragupta Maurya defeated Seleucus Nicator, the founder of the Seleucid Dynasty.

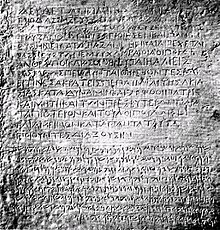

The source of much of our knowledge of Ashoka is the many inscriptions he had carved on pillars and rocks throughout the empire. All his inscriptions have the imperial touch and show compassionate loving. He addressed his people as his "children". These inscriptions promoted Buddhist morality and encouraged nonviolence and adherence to Dharma (duty or proper behavior), and they talk of his fame and conquered lands as well as the neighboring kingdoms holding up his might. One also gets some primary information about the Kalinga War and Ashoka's allies plus some useful knowledge on the civil administration. The Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath is the most popular of the relics left by Ashoka. Made of sandstone, this pillar records the visit of the emperor to Sarnath, in the 3rd century BC. It has a four-lion capital (four lions standing back to back) which was adopted as the emblem of the modern Indian republic. The lion symbolizes both Ashoka's imperial rule and the kingship of the Buddha. In translating these monuments, historians learn the bulk of what is assumed to have been true fact of the Mauryan Empire. It is difficult to determine whether or not some actual events ever happened, but the stone etchings clearly depict how Ashoka wanted to be thought of and remembered.

Ashoka's own words as known from his Edicts are: "All men are my children. I am like a father to them. As every father desires the good and the happiness of his children, I wish that all men should be happy always." Edward D'Cruz interprets the Ashokan dharma as a "religion to be used as a symbol of a new imperial unity and a cementing force to weld the diverse and heterogeneous elements of the empire".

Also, in the Edicts, Ashoka mentions that some of the people living in Hellenic countries as converts to Buddhism, although no Hellenic historical record of this event remain:

Now it is conquest by Dhamma [(which conquest means peaceful conversion, not military conquest)] that Beloved-of-the-Gods considers to be the best conquest. And it (conquest by Dhamma) has been won here, on the borders, even six hundred yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni. Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dhamma. Even where Beloved-of-the-Gods' envoys have not been, these people too, having heard of the practice of Dhamma and the ordinances and instructions in Dhamma given by Beloved-of-the-Gods, are following it and will continue to do so.

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for human and nonhuman animals, in their territories:

Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's [Ashoka's] domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni and where the Greek king Antiochos rules, and among the kings who are neighbours of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. Wherever medical roots or fruits are not available I have had them imported and grown. Along roads I have had wells dug and trees planted for the benefit of humans and animals.

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek (Yona) Buddhist monks, active in spreading Buddhism (the Mahavamsa, XII[9]).

Death and legacy

Ashoka ruled for an estimated forty years. After his death, the Mauryan dynasty lasted just fifty more years. Ashoka had many wives and children, but many of their names are lost to time. Mahindra and Sanghamitra were twins born by his first wife, Devi, in the city of Ujjain. He had entrusted to them the job of making his state religion, Buddhism, more popular across the known and the unknown world. Mahindra and Sanghamitra went into Sri Lanka and converted the King, the Queen and their people to Buddhism. They were naturally not handling state affairs after him.

In his old age, he seems to have come under the spell of his youngest wife Tishyaraksha. It is said that she had got his son Kunala, the regent in Takshashila, blinded by a wily stratagem. The official executioners spared Kunala and he became a wandering singer accompanied by his favourite wife Kanchanmala. In Pataliputra, Ashoka hears Kunala's song, and realizes that Kunala's misfortune may have been a punishment for some past sin of the emperor himself and condemns Tishyaraksha to death, restoring Kunala to the court. Kunala was succeeded by his son, Samprati, but his rule did not last long after Ashoka's death.

The reign of Ashoka Maurya could easily have disappeared into history as the ages passed by, and would have had he not left behind a record of his trials. The testimony of this wise king was discovered in the form of magnificently sculpted pillars and boulders with a variety of actions and teachings he wished to be published etched into the stone. What Ashoka left behind was the first written language in India since the ancient city of Harappa. The language used for inscription was the then current spoken form called Prakrit.

In the year 185 BC, about fifty years after Ashoka's death, the last Maurya ruler, Brhadrata, was assassinated by the commander-in-chief of the Mauryan armed forces, Pusyamitra Sunga, while he was taking the Guard of Honor of his forces. Pusyamitra Sunga founded the Sunga dynasty (185 BC-78 BC) and ruled just a fragmented part of the Mauryan Empire. Many of the northwestern territories of the Mauryan Empire (modern-day Afghanistan and Northern Pakistan) became the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

In 1992, Ashoka was ranked #53 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history. In 2001, a semi-fictionalized portrayal of Ashoka's life was produced as a motion picture under the title Asoka. King Ashoka, the third monarch of the Indian Mauryan dynasty, has come to be regarded as one of the most exemplary rulers in world history. The British historian H.G. Wells has written: "Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history, their majesties and graciousnesses and serenities and royal highnesses and the like, the name of Asoka shines, and shines, almost alone, a star."

Buddhist Kingship

One of the more enduring legacies of Ashoka Maurya was the model that he provided for the relationship between Buddhism and the state. Throughout Theravada Southeastern Asia, the model of ruler ship embodied by Ashoka replaced the notion of divine kingship that had previously dominated (in the Angkor kingdom, for instance). Under this model of 'Buddhist kingship', the king sought to legitimize his rule not through descent from a divine source, but by supporting and earning the approval of the Buddhist sangha. Following Ashoka's example, kings established monasteries, funded the construction of stupas, and supported the ordination of monks in their kingdom. Many rulers also took an active role in resolving disputes over the status and regulation of the sangha, as Ashoka had in calling a conclave to settle a number of contentious issues during his reign. This development ultimately lead to a close association in many Southeast Asian countries between the monarchy and the religious hierarchy, an association that can still be seen today in the state-supported Buddhism of Thailand and the traditional role of the Thai king as both a religious and secular leader. Ashoka also said that all his courtiers were true to their self and governed the people in a moral manner.

Historical sources

Western sources

Ashoka was almost forgotten by the historians of the early British India, but James Prinsep contributed in the revelation of historical sources. Another important historian was British archaeologist John Hubert Marshall who was director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India. His main interests were Sanchi and Sarnath besides Harappa and Mohenjodaro. Sir Alexander Cunningham, a British archaeologist and army engineer and often known as the father of the Archaeological Survey of India, unveiled heritage sites like the Bharhut Stupa, Sarnath, Sanchi, and the Mahabodhi Temple; thus, his contribution is recognizable in realms of historical sources. Mortimer Wheeler, a British archaeologist, also exposed Ashokan historical sources, especially the Taxila.

Eastern sources

Information about the life and reign of Ashoka primarily comes from a relatively small number of Buddhist sources. In particular, the Sanskrit Ashokavadana ('Story of Ashoka'), written in the 2nd century, and the two Pāli chronicles of Sri Lanka (the Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa) provide most of the currently known information about Ashoka. Additional information is contributed by the Edicts of Asoka, whose authorship was finally attributed to the Ashoka of Buddhist legend after the discovery of dynastic lists that gave the name used in the edicts (Priyadarsi – 'favored by the Gods') as a title or additional name of Ashoka Mauriya. Architectural remains of his period have been found at Kumhrar, Patna, which include an 80-pillar hypostyl